Kaija Saariaho: ‘Composing requires patience, but it is a magical thing and a great privilege’

Kaija Saariaho is one of the world’s most prominent and renowned composers who has made herself known both in opera and instrumental music. Her new opera INNOCENCE is scheduled to premiere in Aix-en-Provence in the summer of 2021. I was very lucky to meet with Kaija Saariaho in Paris in December 2019 and asked her tentative questions about her education, her way into music and her being inside it today, her perception of multiple areas that could bring inspiration, the profession of a composer, everyday composition routine, her approach to her collaborators and rehearsal process. I hope that the interview reveals Kaija Saariaho’s unique character and the way of thinking shaped by her Finnish origins and internationally-informed life experience.

Kaija, was it some sort of an epiphany when you suddenly wanted to express yourself in music? Do you remember this source of your future life and career in music?

In fact, music has always been there. But, first of all, I did not even realize that it was a kind of composition when I was imagining music. And secondly, I was very, very shy, so I was not a great instrumentalist, I really hated these performance situations. I come from a non-musician family, so those were my private things - music, and drawing, and painting. It was my world, it is how I was living, and I was quite solitary. Then, at some point - I had been playing several instruments – but then I was thinking that maybe the fact of being so shy and all that, and that I was no virtuoso instrumentalist. So as an alternative how could I be a good composer? I started composing when I was around eleven. It was all quite, you know, I was trying out things, and I had no education on that.

So it was like a self-taught route into composition?

Yes, everything was like that, and even my first instrumental teachers were amateurs, they were not professionals until quite late in my studies. I started playing the organ, and I was still very uncertain about it being my future. Music was really important for me, but I felt that it was a whole way of living and I felt that I am not worthy, I was not good enough for it. So then I was imagining: «What was it like to be an organist?» But I also had been painting and doing lots of graphic work, so that is why then I continued my studying organ, I continued my music education, I studied musicology, and then I studied in an art school. I was studying in three places for a while, and then I got the feeling that I was wasting my time. I was a little bit over twenty, and my life has no meaning if I don’t try to compose. So the music had always been there, but I just did not have any confidence in myself to do it.

I remember that you said you could hear the compositions in your pillow when you were a child like they were coming into your head as dreams.

Yeah, it became a kind of an anecdote, because my mother told me that in the evenings I asked her to «turn the pillow off», because (chuckles) the music was… I was imagining the music came from the pillow and I could not sleep, so I was imagining it, yes… I think I have been always imagining music, but how it was when I was a child, I do not know.

Kaija Saariaho @Andrew Campbell

So in a way composition is something that comes from you, and you have to cope with it, you have to understand what it means and gain the confidence to explore it. Has the source of music for composition always been inside, or outside yourself?

I am sure there have been enormous influences. All the influences, you react to them inside yourself, and then they become a part of your subconsciousness. So only afterward they come from me… but there are many many influences, but we are not aware of them, really.

So in a way is it almost like in Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of practice where the knowledge becomes a practice that you are not aware of.

Well, that is how it should be. Of course, compositional work is very much… well, it is so interesting, because it involves very much thinking, but yet you have these different feelings about music you want to write, and then, when you really need to do an important move in composing… All the time you make so many rational decisions, but yet, maybe the most important decisions on your composing table are when you suddenly have something like a wild feeling that now you know how things go, those are intuitive decisions, but of course, intuition is not a black hole.

I was surprised that you have said you can work on your intuition, you can not wait until it comes, you should approach it every day. It is similar to what Konstantin Stanislavski said: the actor should not wait for inspiration but go to meet it every day. Is it like this, do you meet your inspiration?

I think it is so in all arts. Think about musicians or sportspeople. Is it nice to warm up every day? Well, it is not, but you know that it makes you get in into your thing, and I think, in a way, it is completely similar in the composition process.

Can you now, retrospectively, say what has been more influential for your future development: your Finnish studies at Sibelius Academy with Paavo Heininen or your work in Freiburg or Paris? Which roles did these three different schools play in your future career and at what point do you think you found your voice?

Well, without any doubt, the most important thing was my studies with Paavo Heininen, but it is because before that I was nothing. He somehow forced me to do all the work and to do a lot of conscious work. I was very intuitive, and he really taught me how I can learn to compose, and how I can continue teaching myself. All that came after – it was very important, but if I would not have had that beginning, I do not know what would have happened. But, you know, there is something already in my first compositions that I still recognize very well, but then it took many years for it to grow into something more personal, fully personal so that now someone from outside can easily recognize my music. But it is the same way, the more technical skills you get, the more you get into yourself, and the more you get confidence in yourself.

Could we compare composition to an archeology of self? A process where you carefully learn the rules of going inside yourself, like almost in an ancient Roman town, and discover things inside you.

Kaija Saariaho @Maarit Kytoharju

I think in my case – yes, indeed. I am sure every composer is so different, but because I had this relation to the music from the beginning that I felt when I was a child – I felt that music was like magic – that it was so strong, that I was afraid of it, I loved it, I had so many feelings about it. Then, I began to explore where was my place in all that, and what was I. One of the reasons was, of course, that when I was young and interested in composition, everybody was saying that it makes no sense. Look around you, they said: there are no girls who are doing it. And I was thinking that myself: «I am here, not a great instrumentalist, a shy girl, not coming from a cultural family. So how could I do something that no girl, no woman made before me?» And what I really did not like was the idea that I will do some kind of boring, mediocre music. I knew that the world is so full of that music. On the other hand, then, when I overcame this crisis and decided that I would do it anyway, then I could not think about that anymore in that way. I could not think about whether there is musical value in what I was doing or not. It did not matter because then for me the music was so important, that I just needed to do it.

It is almost like the power of expressing it became stronger than your fear of doing it?

Little by little, yes.

And what was the role of your colleagues from Korvat Auki group, your friends – Magnus Lindberg, Esa-Pekka Salonen, the cellist Anssi Karttunen and the clarinetist Kari Kriikku. How did they inspire you, did they help you to feel more confident? What was the role of this group, and why the connections between you still remain strong?

Well, Korvat Auki group was really important during my studies because we… there were many other things that we would have liked to study, but it did not happen at the Sibelius Academy. So we started organizing these studies by ourselves: different kinds of seminars and analysis, and of course they always finished with nice parties, but the work was very serious. In a way, the most difficult task was to present something to your close friends. It was quite a group of people, and those people remain important to me. Then, of course, everybody went their own way and for different reasons, Esa-Pekka and Magnus have remained very close. Anssi lives here in Paris, and we have been long-time friends – not specifically for that reason, but also partly because of that.

Can you talk a bit about the influence of Gérard Grisey and your interest in electronic music? I have read about this piece called Stereophonic Play which combines noises of trains and poetry… what were you trying to do with this use of electronics? And can we say that you tried to analyze the sound, the nature of sound through doing this?

I did a lot of things, really a lot, a lot of things in this field. I started working with electronics already when I was at the Sibelius Academy, because I became interested in amplifying sound, so that some very soft things can be better heard, because the places where our music was played were not very nice, they were not like concert halls. And then, little by little - in Freiburg I also worked in a studio, and then when I went to Paris, I applied to IRCAM, and then it was the time to explore it fully. A year before that I heard for the music of Gérard Grisey and Tristan Murail for the first time in Darmstadt, and at that time that was completely unbelievable, because we were living in a post-serial era, and in Germany there started a counter-movement which was some kind of neo-romantic music. But what I heard one summer in Darmstadt was completely unheard of: it clearly followed the music of Debussy or Ravel may be, and yet it sounded completely different. And afterward I learned to know Gérard Grisey and Tristan Murail, and I learned how they worked, and it happened in Paris. There were two important studios: one was IRCAM but the other one was in the French Radio House – GRM (Groupe de Recherches Musicales) – and they had really, really interesting things going on. They came from this musique concrète movement where you only manipulated concrete sounds. Sometimes they became abstract through the manipulation. In the meanwhile, at the IRCAM the idea was to do everything digitally so that you created sounds digitally, and for that, you need to have very much knowledge of acoustics and physics and all that. I was interested in both of these movements, and that is why I worked in both studios.

Stilleben that I wrote then was a radiophonic piece - it was made for radio. The challenge when writing it was to write a big orchestral work but instead of orchestral instruments I had vehicles, I had different languages, I had recordings from Lichtbogen. I had all these voices and it was like a musical score. Then I also wanted to give poetic content to that work but expressed also in abstract musical forms. That was one of the ways in which I was trying to break the boundaries and was making research within these associations’ sphere of interests. The interesting thing about the concrete sounds is that it adds a layer like text always adds a layer, but the one made in concrete sounds. If you hear in my piece the sound of the metro doors closing, then it reminds you – in addition to the abstract experience, it reminds you of your experiences. So I was very much interested in research in electronic music. I still am, of course, and, in a way, in the operas, too, and in a way I am still dealing with the same things.

Kaija Saariaho @Maarit Kytoharju

But then, coming from this IRCAM side was the finding that every sound has its own spectrum. And when you have a whispered sound, or wind, or something else which has a lot of noise, then the spectrum is not mathematically symmetrical at all. There are so many components in it, and that is why we do not hear one pitch, we hear the noise. And then, on the other hand, any instrument playing a pitch has a spectrum which is much more regular. I liked to also organize these concrete sounds according to their acoustic nature. So I was in the middle of many different influences and I wanted to find my music in the middle of them all. I come from Finland, I spend so much time in nature, so in a way I feel that nature… there is no boundary, and nature can be part of the music, that’s why I always explored these interconnections between different approaches to music.

In terms of this boundary-crossing, do you think that in music these different elements could be brought in: architecture, literature, sounds of nature, train sound? You have this piece D’OM LE VRAI SENS whereas I understand you explore these interconnections…

I was very impressed how you tried to explain your idea behind it: you wanted to show how smell works through music, how touch works through music. Do you still feel that these non-musical elements and perceptions can be expressed in music?

No, not really… but it is very inspiring to think about it. There is always a starting point for everything, and the idea of composing smell it is of course a great idea. But am I really doing it? No. Because, in a way, I let this wonder in my mind and imagine what kind of things it would invite, and then I get to my composition, and when I do it, in fact, it remains only musical composition.

So when the piece is dedicated to an architectural building, for example, Wing on Wing by Salonen, then it is only a starting point and not an expression of architecture in music?

I think you should ask Esa-Pekka, because everybody is working so differently.

You mentioned that you like to work through intuitive associations, and that also interests me because much of the knowledge that we need is coming through intellectual activity. Only several arts activate our intuition: for instance, poetry is based on your associative mind work, and of course music. Do you think that in our modern world it is a necessary addition, almost a medicine for a brain as we are now so overwhelmed by scientific knowledge that we need to develop this associative thinking? Do you think that music is a way to increase our capacity to be poetic inside, to be associative, to be actually able to connect our intuitions with the outward realities?

All arts are. All arts are, and I think with music we still do not really know about how it works, because it is like a smell. We smell so many things and yet we do not know about it, but it really affects our way of doing many things. I think it is a little bit the same with music: it can somehow go deeper than words. At the moment the society has become crazy, everything is completely commercial, everything is valued by monetary value, and education at art schools for children is diminishing, I think this is all horribly dangerous for humanity. I mean, how do we learn empathy? How do we learn to understand how somebody else can feel? How can we put ourselves to that place? How can a child learn to do it, how can we learn to accept that we do not agree, but it is still ok, that everybody can be a different individual? I think art has so much to teach us. And yes, in our adult age music is a fantastic liberating place, it really is, and it inspires us.

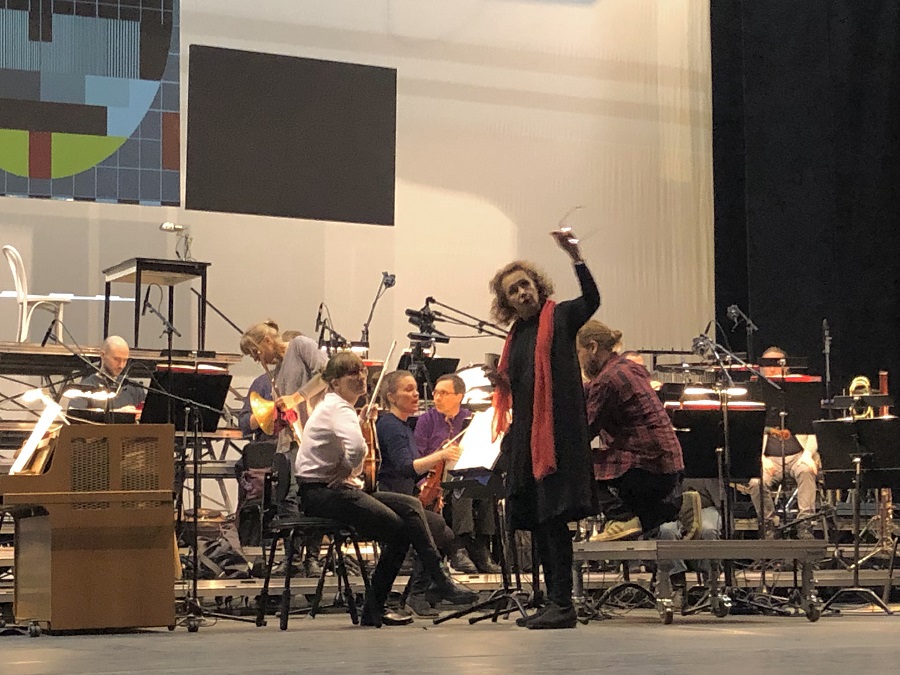

Kaija Saariaho at the rehearsals of La Passion de Simone by La Chambre sux Echos @Jari Kallio (2019)

So in a way it has an ethical dimension, music is doing good in its own way, it could be part of ethics and religion for someone, an escape route from the commercial relations that you have described. Are we coming to the concerts to escape reality or to live in it?

I do not think that you need to escape something, I think you escape things when you go to events with pure entertainment, there indeed you escape reality. But I do not think we escape reality by attending classical music concerts. It is an important part of reality, it is part of everything that is surrounding us… I do not see it like escapism, you know. But there are fine lines everywhere. What is spirituality? How much spirituality is in knowing about yourself, and can it be called escapism? For some people, it is indeed an escape, and they need it really badly.

Can you return to your work with instruments, including voices? You mentioned that the cello is one of your favorite instruments to work with, I guess maybe because of its resemblance to the human voice. Then you also have a Clarinet Concerto and pieces where a harp is a leading instrument. I wanted to ask when you focus on a piece where a certain instrument is the leading one, how is your thinking developing? Do you have to go through the whole repertoire that exists for this instrument? Do you have to work a lot with the soloist who is the professional on this instrument? How do you explore the potential of the particular instrument when you compose a piece for it?

It comes very naturally. I have an affection for different instruments for different reasons: cello for the reasons you mentioned, but also because it is very well-suited to make very fine things with the harmony and changes of a bow position. And of course, the ambitus (like tessitura for voice) for this instrument is very big, so it is very comfortable for a certain kind of color thinking. In fact, I enjoy all string instruments very much, because both hands a lot of fragile work, and so the color palette is very developed. I also like the flute very much, and for different reasons. With flute you can start with pure breath, and then very gradually go to pure flute sounds, you could do these transformations very, very gradually. So there is this kind of initial interest when composing for a certain instrument. And this interest had led me to explore the pieces for them, so when I start I have already known and listened to a lot of repertoires, and then, at some point, there can be an encounter, it can come from me, or it just happens. I feel that there is the right kind of person for who I want to write this music. There is not much of any kind of workshopping with them. It is rather that I write my music and then we have a look together with the musician. Is everything comfortable, are there some things that are uncomfortable, have I been overestimating some things? I always try to think very physically and with the application of my thought to a particular instrument.

Kaija Saariaho at the rehearsals of La Passion de Simone @Jari Kallio (2019)

Isn’t it a paradox that you think of the real person who will play your music – your collaborator – but then there is a score that in theory, anybody could play in 100 years? Can you envision your music not being played by the people you intended it for but by somebody else?

Oh, it happens all the time. It happens. Even a Harp Concerto has by now been played by many people. It happens, it is normal, I am happy about that. It is not similar in each case, but it remains my music. It has to be born, it needs to have special conditions for it, and when it is being born, when it is starting its life, I am very happy if it starts with someone who really knows my music. Then, the beginning is good, and then afterward it could develop into different directions.

As a modern composer, are you constantly aware of all the previous existence of music, like I a modern writer would know of Tolstoy, or Proust? Is there pressure from the fact a composer and that there is a line of other composers before you? Do you think about it, do you think in terms ‘I am within this tradition, I have quoted this extract of Stravinsky’? Do you relate to previous generations in your mind when you compose?

No, not really, but of course I am aware of its existence. I come from that tradition, and there have been fantastic composers in history that I admire very much. But I feel that my music is my music. I very rarely take anything, at least consciously, from somebody else’s music. But, well, when I was younger there were some thoughts in this vein. For example, when I wrote my Violin Concerto – Graal théâtre – it was my first Concerto. I thought how could I write a violin concert? There are so many fantastic concertos that mine could never be as fantastic. But then, at some point, I just thought, well, I am writing my Concerto today, and it will be what it will be, and it will be my music. It was so charged, the stakes were so high, and I had such strong feelings about many other violin concertos that yes I always related to them when composing…. but after that, I think the door was opened.

Is it difficult to be original or you do not think about it? Do you have these self-doubts: «Am I original enough»? How does one deal with self-confidence at the mature stage of being a composer?

As I said before, I think we are all so different… No, I cannot ask if I am original enough, or I cannot ask if my music is good enough. I just need to create conditions, specific conditions, in which I can do my best. I must not be too much in a hurry, I want to keep myself in good health, Those are completely practical things, and I need to do my best during my composition time. At least it does not have to do with time. I need to have enough time, and that is the most difficult thing. And if it is not good enough, anyway, it is never good enough for everybody, so what can I do? (chuckles)

Kaija Saariaho @Maarit Kytoharju

Can you describe the daily routine of composition? Maybe at its early stage, maybe at its late stages? What exactly is happening on your day of composition?

Well, I start composing in the morning and I do not make many breaks. I make a break to have a little lunch and then I continue to compose. I force myself to be in front of my work in the mornings. Sometimes I am very eager to do that, sometimes I am not, but even if I am not I try to get myself going. As I described, the initial resistance oftens happens but then you warm up and you are able to continue your work. However, this does not always happen, but one always has to try. So basically I try to keep myself working. I have had different periods in my life. When I was young, sometimes I did not even know what weekday we were living in (chuckles), as I was just working all the time. Then when I got children, for about twenty years of my life I had to adjust myself to their schedules. Here in France the schooldays are quite long, so I divided my life between composition and the role of a mother. Now when they are adults, I am back to a more total way of living in my music. There is nothing special, I just need to have a lot of time and patience, and continue to compose.

Do you use computer programs for composing or you manually write your scores?

I do use them. Sometimes I write by hand, but normally I use the Finale program, and when I have all the notes as I want them, then I print a page, and then by hand, I add dynamics and other nuances, and these days now I scan the page and send it to my publisher for them to finalize it.

Then I wanted to turn to your productions for voice: your operas and the oratorio La Passion de Simone. You have mentioned before that there is a paradox between composition being a lonely process and the intensely social and theatrical element of performance. With opera in particular, what is your process of thinking, do you try to imagine it on stage when you are composing, or do you leave this envisioning for your collaborators? Can you describe your work with the librettist Amin Maalouf and with opera director Peter Sellars? What is the process of working on the opera, and can you describe your new opera INNOCENCE?

Yes, working on the opera is of course a very long process. The first opera, L’amour de loin, was the longest because I needed to understand that I wanted to write an opera, and then the question was what kind of opera. I did not know how to look for partners in opera creation, so it took a long time. I had my chosen subject matter but I needed to find a good librettist who was the right person, and then I found Amin Maalouf. I knew Peter Sellars’s work, but it took a long time until we came together to collaborate. The timeline for opera writing is always similar: at first, there is an idea or a feeling that you want to write an opera. When I wrote L’amour de loin, I thought it will be my only opera, I had no intention to write more than one. First, there needs to be a libretto, otherwise, you cannot compose the opera. Then you have the composition period when you are completely alone. With L’amour de loin I did try to imagine all kinds of stuff on stage, but Peter did not want to hear about it, as he wanted to think about his things. Only later I told him about things that I was seeing, and in fact, he realized it, although in his own way. He also did many things that I did not think of, and many things I did imagine did not ever happen. What I think about this collaboration is that I am the professional of the composition, and then I work with other professionals, and that is the interesting thing about opera — how to come together. And if it is the right person I do not feel offended by new suggestions, I am rather interested. Every time it is a process that takes a long time and every time happens in a different way. Every time there are big crises at some point. Often they do not concern me, but other members of the creative team, as there are so many big egos in the same room. Some tensions can happen with singers, with stage directors, with conductors, often between a stage director and a conductor. The only instance where there was no such tension was between Aleksi and Clement in staging La Passion de Simone but for them, it was their starting point, that is why they have created their company – to work together. But in this kind of typical opera house situation, everything is very fixed, and it actually tries to make things work through these different egos not meeting too often. Normally, I do not want to get involved too much. If I really feel that something is going amiss in my music, of course, I try to intervene but otherwise I try to let things go as they are.

Kaija Saariaho at the performance of La Passion de Simone @Jari Kallio (2019)

With your new opera INNOCENCE did you have to live with the material for a long time? Can you describe Sofi Oksanen’s text? Did you have to read many other materials? How do you immerse yourself in the material which you will write an opera about?

In INNOCENCE I worked on the original text, Sofi’s text was written for me. And so we’re all the other librettos for my operas, except for Only the sound remains, where I dramatized it myself as there is so little text anyway. If I felt that something was unnecessary, I just did not use it. So with every text, I have been with it from the very beginning, so I internalized it, made it my own in that sense. When I write an opera I am hardly reading any books. I just work with the libretto. It is very typical, because what makes the opera tiring for me — I do not know what Verdi did as he wrote so much and so quickly (chuckles) – but I feel I need to psychologically understand every part.

To go into the minds of your characters?

Yes, I never wanted to have black-and-white stories where someone will be good and his counterpart will be bad. I think that is a very big mistake of western storytelling to make those kinds of simplified persons. Nobody is in fact like that. I have always been rather interested in different sides of my characters. So in a way, I had to try to become those persons. When it happened to me for the first time with L’amour de loin, when Jaufré Rudel [the main character who is a troubadour in 12th century France] dies, when I knew that Jaufré will die soon, I started to feel relieved, and feel, that, you know… one less!

You could do an Agatha Christie kind of opera where the characters gradually die one after another and it becomes easier and easier…And you always say that you always think of particular interpreters, like there is a song cycle for Anu Komsi, a mono-opera for Karita Mattila, so I guess there is one more character to get under the skin of, which is the singer, in this case, because you said that you explore them, so deeply – and then you write for particular people to interpret them.

Yes, but in a way it is also an additional inspiration, in a way, it is easier to write for them when you know these persons that will interpret your work.

Can you describe how you work with the conductors? What is your role when you meet a conductor during a rehearsal of your work? How can a composer transport her views apart from what is already written in the score?

That is a very good question, and it is very difficult. It is really something difficult to describe… it is like love, or friendship, or something similar. Either it works or it does not work. And sometimes people can grow to like each other. Some sometimes they like my music, and sometimes they do not, that is why I value certain conductors who know my music so much. It is very difficult to verbalize things like breathing, or the importance of certain colors and balance. There is a certain sensory in my music that has to do with these colors, and not everybody is sensitive to that. Also, there is a more regulative thing about structure… and if somebody is not paying attention, if they do not feel it, the musicians themselves begin to realize that they do not feel it, and then these conductors are not transmitting it to musicians. I just have accepted that that is how it is in some cases. But the only thing I regret is that I often I cannot propose (chuckles) conductors for important things. It has also become a business, and business negotiations have to do with fame and money, those kinds of things. If they were done according to who has more time and a lot of affection for my music, it could have been a better choice musically.

Can you imagine how the listener feels? How much trust an unknown group of people in a concert hall or an opera house to understand your music? Are there a layer that a mass audience will understand, and another layer that only an educated audience will get?

No, I do not think that audiences can be divided into groups. That is why conductors and all musicians are so important. I mean, it depends very much on what kind of performance it is. When it is a performance done by a conductor who trusts my music, everybody can hear its different layers. That is how it is. If the conductor steps in and conducts through my score and makes it like his passing job, everyone can hear the difference, the music becomes very boring. The audiences react depending on what they get, and in what way they get it. I do not think there is a body of the audience as such, there are just persons and everybody comes to their lives, maybe someone has had a bad or a good day. They come together in this collective experience, and in that sense attending a concert is spiritual. If you go to church and you listen to a priest speaking it can be fantastic and interesting, or it can be very boring – the same is with music.

Is the spiritual element lost in the recording or video?

I do not think so — not necessarily. It depends, again, it depends on you: how do you listen to it?

You are using literature a lot: texts, poetry. You mentioned that you sometimes go back to your favorite authors and books and search for inspiration. What is your reading sphere? Is it poetry? How do you discover texts for your works and select your reading materials?

It is different every time. It can be a text that I find accidentally, it can be a text I want to go back to. Recently I asked my son Aleksi to discover something new for me. It is just an encounter, it needs to be the right one, but every time it is different.

Kaija Saariaho @Maarit Kytoharju

What are the languages that you read?

Finnish, French, English, Swedish, German… those are the languages I speak. Then recently – for INNOCENCE – I used other languages, and that was interesting a real challenge.

Can there be an opera based on a libretto written in a nonexisting, invented language?

People are doing it indeed. It is not possible for me, but in general, it seems to be possible. I am a very old-fashioned person in this sense. I really like to have a storyline in the opera even it is more or less abstract. What I myself like in an opera experience and that is how it is different from going to a concert: there relate us as human beings to the characters in the opera, to their lives and their decisions, and what they are going through. That has started to interest me when I turned to the oper – how it is different from abstract feelings and reactions we have when we normally go to concerts.

What are the most difficult things in being a composer? And what sides are enlightening, happy, and rewarding?

Well, I think about it every day (chuckles). It is difficult because it is very solitary work, it is very slow work. This is why I am spending all my life composing. It requires a lot of patience, What is fantastic is, of course, when you have this moment when you suddenly know what to do… and also sometimes, but not often, when you hear your music, and when you feel there are some things that really communicate something — it is a magical thing, it is a great privilege.

Is it similar to an epiphany coming from above?

I definitely can not imagine it coming from me. If there is something very fantastic, I never think, oh, that comes from me. I just think that it is very beautiful. So maybe I think it came through me. But I am not a religious person so I never consider it as an epiphany coming from a certain deity, no. Well, it seems good to finish here, as we are entering a complex subject matter (chuckles).